.

Dr. Yamuna Krishnan

Professor, Department of Chemistry, University of Chicago

Yamuna Krishnan was Senior Assistant Professor at the National Center for Biological Sciences (NCBS), Bangalore, India

Yamuna Krishnan was Senior Assistant Professor at the National Center for Biological Sciences (NCBS), Bangalore, India

Born, Chennai, India, 1974

Madras University, B. Sc., 1993

Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore, M.S., 1997

Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore, PhD, 2002

University of Cambridge, UK, Postdoctoral Fellow 2001-2005

National Centre for Biological Sciences, Bangalore

Fellow 2005-9

Reader 2009-13

Associate Professor 2013-14

University of Chicago, Professor 2014-

Accolades

2014 AVRA Young Scientist Award

2014 Faculty of 1000 Prime, Chemical Biology

2013 Associate Editor, Nanoscale, RSC Journals

2013 Editorial Advisory Board, Bioconjugate Chemistry, ACS

2013 Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar Award, Chemical Sciences

2012 YIM-Boston Young Scientist Award

2010 Wellcome-Trust-DBT Alliance Senior Research Award

2010 BK Bachhawat Award

2010 Editorial Advisory Board, ChemBiochem, Wiley VCH

2009 Indian National Science Academy’s Young Scientist Medal

2007 Innovative Young Biotechnologist Award

2003-5 Fellow of Wolfson College, University of Cambridge, UK

2002-4 The 1851 Research Fellowship from the Royal Commission for the Exhibition of 1851

1995-6 SK Ranganathan Scholarship

Studied at Women's Christian College, Chennai

Lives in Chicago, Illinois

Yamuna Krishnan

Professor, Department of Chemistry, University of Chicago

email.......yamuna @ncbs.res.dot.in

E-MAIL: yamuna@uchicago.edu

cv....https://www.ncbs.res.in/sitefiles/YK-CV-14.pdf

https://twitter.com/krishnanyamuna

http://www.researchgate.net/profile/Yamuna_Krishnan2

https://www.facebook.com/yamuna.krishnan

- May 3, 2011 - Yamuna Krishnan is Senior Assistant Professor at the National Center for Biological Sciences (NCBS), Bangalore, India. She already ...

Yamuna Krishnan | LinkedIn

https://www.linkedin.com/pub/yamuna-krishnan/6/8a2/81bGreater Chicago Area - Professor, Department of Chemistry, University of ChicagoView Yamuna Krishnan's professional profile on LinkedIn. LinkedIn ... Current. National Centre for Biological Sciences,; National Center for Biological Sciences.

Women in Chemistry — Interview with Yamuna Krishnan ...

www.chemistryviews.org/.../Women_in_Chemistry__Interview_with_Ya...

Yamuna Krishnan (born 25 May 1974) is a Professor at the Department of Chemistry, University of Chicago, since August 2014. She was earlier Reader in National Centre for Biological Sciences, TIFR, Bangalore, India. She is the youngest woman recipient of the Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar Prize for science and technology, the highest science award in India, which she won in the year 2013 in chemical science category.[1] She earned her Bachelor's in Chemistry from Women's Christian College, Chennai in 1994. She secured MS in chemical sciences in 1997 and PhD in organic chemistry in 2002 both from Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore.[2] Her current research interests are in the areas related to structure and dynamics of nucleic acids, nucleic acid nanotechnology, cellular and subcellular technologies.[2] She was a recipient of the Wellcome Trust -DBT Alliance Senior Research Fellowship in 2010, the Indian National Science Academy Young Scientist Medal in 2007 and of Innovative Young Biotechnologist Award from the Dept. of Biotechnology, Govt. of India, in 2006

Education Details

Ph.D (Organic Chemistry):Jan 2002, Department of Organic Chemistry,Indian Institute of Science,Bangalore, India. M.S. (Chemical Sciences):Sept 1997, Chemical Sciences Division, Indian Institute of Science,Bangalore, India, B.Sc. (Chemistry):Jun 1994, Women’s Christian College, University of Madras.[2]Professional Experience

Her professional experience began as a graduate student at the department of chemistry at Indian Institute of Science from 1997 to 2001. She worked as a post doctoral research fellow and an 1851 Research Fellow from 2001 to 2004 at department of Chemistry at University of Cambridge, UK. She was a Fellow 'E' at National Centre for Biological Sciences from 2005-2009, TIFR, Bangalore, India and then tenured Reader 'F' from 2009-2013 at National Centre for Biological Sciences, TIFR, Bangalore, India. In 2013 she was worked as an Associate Professor 'G' National Centre for Biological Sciences, TIFR, Bangalore, India and moved in August 2014 as Professor of Chemistry at the University of Chicago.

References

1"Dr. Samir K. Bramhachari Announces Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar Award 2013". Press Information Bureau, Government of India. Retrieved 30 December 2013

2 "Curriculum Vitae of Yamuna Krishnan" (PDF). NCBS. Retrieved 2 January 2014.

2 "Curriculum Vitae of Yamuna Krishnan" (PDF). NCBS. Retrieved 2 January 2014.

External links

Experience

Associate Professor

National Centre for Biological Sciences

Education

Indian Institute of Science

Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.), Organic Chemistry

Women's Christian College

Bachelor of Science (B.Sc.), Chemistry, 1st with Distinction

Activities and Societies: Years II & III: College Quiz Club Coordinator (Sr), College Magazine Ed Board

Honors & Awards

Additional Honors & Awards

Jun 14: Council Member, Chemistry Biology Interface, Royal Society of ChemistryJun 14: Faculty of 1000 Prime, Chemical Biology

Jun 14: AVRA Young Scientist Award

May 14: Cell's 40 under 40 - next generation's thinkers in Biology

Apr 14: Editorial Advisory Board, Bioconjugate Chemistry, ACS

Sept 13: ShantiSwarup Bhatnagar Award, Chemical Sciences

Jul 13: Associate Editor, Nanoscale.

Oct 12: YIM-Boston Young Scientist Award

Oct 10: Editorial Advisory Board Member, ChemBioChem

May 10: Member, Global Young Academy

Apr 10: Wellcome-Trust-DBT Alliance Senior Research Fellowship

Jan 10: BK Bachhawat Award

May 09: Indian National Science Academy (INSA) Young Scientist Medal.

Feb 07: Innovative Young Biotechnologist Award

Jun 05: Young Associate, Indian Academy of Sciences

Oct 03: Fellow, Wolfson College, Univ of Cambridge

Oct 02: 1851 Research Fellowship from the Royal Commission for the Exhibition of 1851.

Aug 96: SK Ranganathan Scholarship

2011 was the International Year of Chemistry (IYC 2011) and the centenary of Marie Curie’s Nobel prize in Chemistry. Therefore, ChemViews will introduce interesting women throughout the year.

Yamuna Krishnan is Senior Assistant Professor at the National Center for Biological Sciences (NCBS), Bangalore, India. She already performed a remarkable career, is enthusiastic not only about bringing chemistry into biological systems as well as teaching students and she lives Mahatma Gandhi's 'Be the change you wish to see'.

Tell us a bit about how your career has developed?

I did my Bachelors in Women’s Christian College, a small but

well-known college in Madras, India. Then, I was accepted into the best

PhD program for chemistry in the country at the Indian Institute of

Science, Bangalore, where the freedom my PhD supervisor gave me really

allowed me to grow into chemistry in its broadest sense. As if this was

not enough, I later found myself working at Cambridge University with

Shankar Balasubramanian, a young and dynamic chemist, a deep thinker and

excellent mentor. By just observing him I learnt a great deal in terms

of how to identify and approach scientific problems. When I was applying for positions back in India, by sheer chance I visited the NCBS – the scientific atmosphere and the quality of the people there completely re-oriented my plans and I could not picture myself anywhere else. The environment of this biology-centred institute was what enabled me to take our chemistry into biological systems.

So a series of fortunate accidents or opportunities, however you see it, is the way I would best describe how I got to where I am.

What do you enjoy most about your career?

Working with people who share a youthful enthusiasm about science.

Biologists are remarkable people, and I’m fortunate that I can interact

with a wide selection of the best at NCBS. I enjoy exploring the breadth

of biology that is still inaccessible due to lack of the appropriate

chemistry to capture its workings. And of course, the joy of watching

raw students slowly and surely turn into high quality scientists.

When did your interest in sciences begin?

I have been interested in science ever since I can remember. I used

to grow sugar and salt crystals, dissect flowers and dead frogs (with

kitchen knives!), repeat all the little experiments at home that we used

to read about in school.In short anything possible with the resources of Mum’s kitchen and Dad’s garden.

How did you decide to become a chemist?

My entry into chemistry was an accident. I wanted to do architecture,

but ended up settling for chemistry as a compromise, since my marks in

Math in a particular crucial exam were not enough for me to make it into

the Architecture course. I am now very happy I did not do architecture!

What has been your biggest motivation?

My biggest motivation is to improve my understanding of the chemistry

of nucleic acids within the cell and enjoying that journey with my

students. I cherish working with such motivated and intelligent

youngsters, and at the end of every day I can’t wait to get back to the

lab again and enjoy growing together as we gain control of our

scientific problem.

Do you think there are still differences between men and women in chemistry?

Were there ever any?!! In my mind, there are none. I know that my

parents would not have raised me any differently had I been a boy, and

maybe this is the reason I see and feel no differences between men and

women in science.

Have you experienced any personal struggles typical for women in sciences?

Personal and professional struggles are part and parcel of everyone’s

career and I too have undergone my fair share at every stage – but I

have never considered that any of them was because I was a woman. We all

go through struggles, whether we are men or women.

What advice would you give other women thinking of embarking on a

scientific career?/What was the best advice you have ever been given?

If you don’t struggle for something, you will value it less when you

get it. The harder the struggle, the sweeter the fruit. I believe that

if you want something badly enough, you will find a way to make it

happen. The words I always remember are those of a dear teacher,

collaborator and friend Sandhya Visweswariah who said – work is a reward

in itself – it helps me through good days and bad.

What do you do in your spare time?

I do a lot of sport. I go running, swimming, I travel, read books,

watch movies, go to music concerts and spend time with my parents.

What would you like to be doing ten years from now?

Gosh, I can't think that far ahead! Things change so fast in science!

But five years from now I hope to revolutionize the way we visualize

proteins inside living cells. And I hope to be working with students who

are as great as those I’m working with now!

What else would you like readers of ChemViews to know about you, your

experiences, or women in sciences in your country or in general?

Whether you are a man or a woman, if you wish to see more women in

science, to quote the great Mahatma Gandhi, be the change you wish to

see.

Thank you very much for this interview.

| chemistry, Biophysics and Bioinformatic | ||

Y A M U N A K R I S H N A N |

RESEARCH I LAB MEMBERS I PUBLICATIONS | POSITIONS | ALUMNI | |

| Our group is moving to the Department of Chemistry, University of Chicago.

https://chemistry.uchicago.edu/faculty/faculty/person/member/yamuna-krishnan.html

We have had a GREAT time at NCBS, a very special place indeed and continue to cherish our strong ties here.

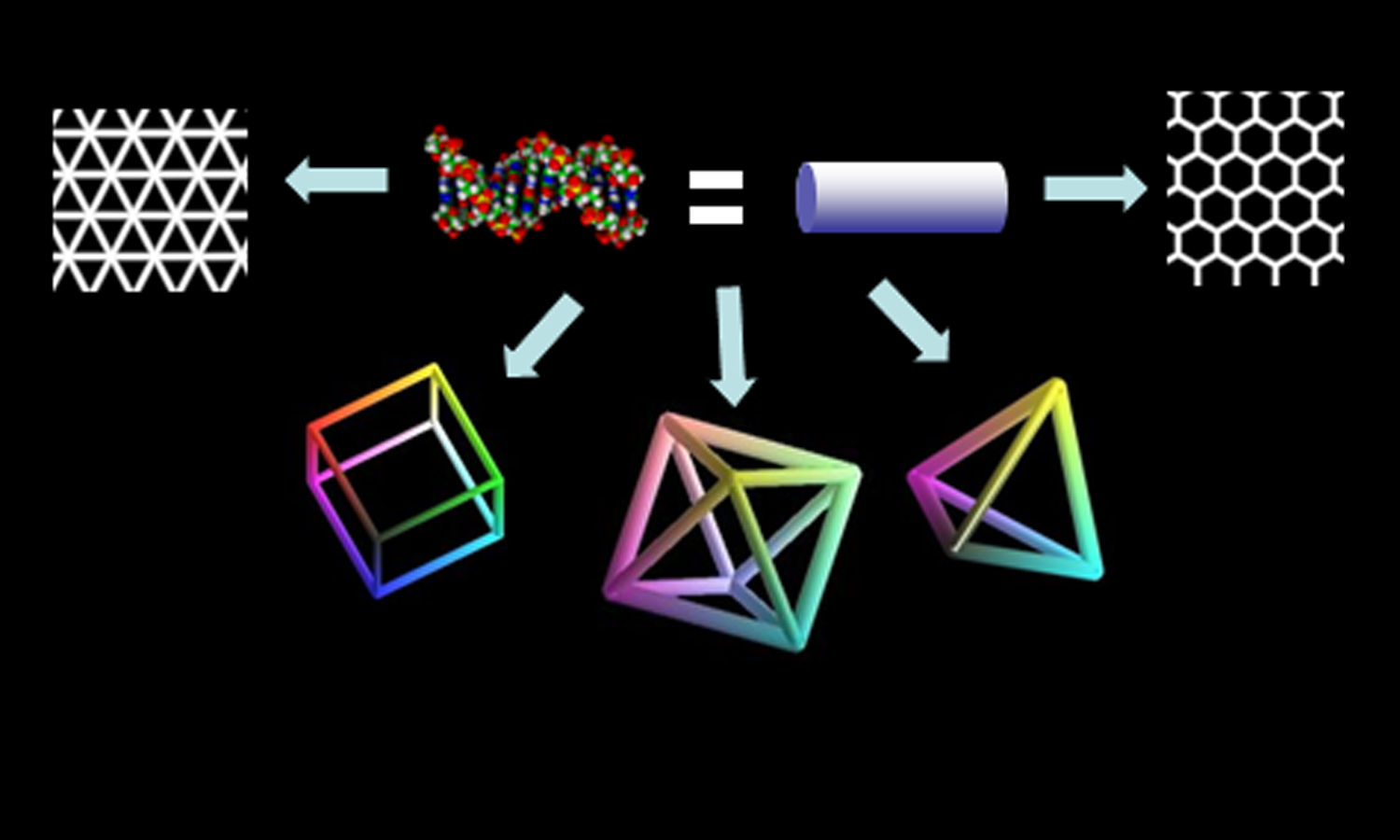

Structure and Dynamics of Nucleic AcidsBionanotechnology aims to learn from nature - to understand the structure and function of biological devices and to utilise nature's solutions in advancing science and engineering. Evolution has produced an overwhelming number and variety of biological devices that function at the nanoscale or molecular level. My lab’s central theme is one of ‘synthetic biology’, which involves taking a biological device, component or concept out of its cellular context and harnessing its function in a completely new setting to probe, program or even reprogram living systems. Our current research involves understanding the structure and dynamics of unusual forms of DNA and translating this knowledge to create DNA-based nanodevices for applications in bionanotechnology. Structural DNA nanotechnology is an emerging field that uses the base-complementarity design principle of DNA to create ordered superstructures from a set of DNA sequences that self-assemble into regular, well-defined topologies on the nanoscale. With a diameter of 2 nm and a helical periodicity of 3.5 nm, the DNA double helix is inherently a nanoscale object. The specificity of Watson-Crick base pairing endows oligonucleotides with unique and predictable recognition capabilities. This makes DNA an ideal nanoscale construction material. Understanding and thereby controlling structure and dynamics in DNA is thus key to realizing its potential as a nanoscale building block for device applications of structural DNA nanotechnology. These DNA nanodevices may function as rigid scaffolds in 1D, 2D or 3D or as dynamic switches. Selected Publications:

If you've reached this far, see some features on our work! http://www.nature.com/nindia/2013/130528/full/nindia.2013.69.html http://www.nature.com/nnano/reshigh/2011/0611/full/nnano.2011.91.html http://www.nature.com/nindia/2011/110629/full/nindia.2011.99.html http://www.financialexpress.com/news/giving-dna-nanodevices-a-new-role-inside-living-systems/875447/0YK's Full CV Lectures Delivered  | ||

OFFICE:

E305A, Gordon Centre for Integrative Science

E-MAIL: yamuna@uchicago.edu

Bionanotechnology aims to learn from nature - to understand the structure and function of biological devices and to utilise nature's solutions in advancing science and engineering. Evolution has produced an overwhelming number and variety of biological devices that function at the nanoscale or molecular level. My lab’s central theme is one of synthetic biology, which involves taking a biological device, component or concept out of its natural cellular context and harnessing its function in a completely new setting so as to probe or reprogram the cell. Our research involves understanding the structure and dynamics of unusual forms of nucleic acids and translating this knowledge to create nucleic acid-based nanodevices for applications in biology.

Synthetic DNA nanodevices

Structural DNA nanotechnology is an emerging field that seeks to create exquisitely defined nanoscale architectures via the self-assembly of a set of carefully chosen DNA sequences. With a diameter of 2 nm and a helical periodicity of 3.5 nm, the DNA double helix is inherently a nanoscale object. The specificity and predictable affinities of Watson-Crick base pairing affords a hierarchy of molecular glues between given rods at defined locations that makes DNA an ideal nanoscale construction material. DNA nanodevices could either be rigid scaffolds in 1D, 2D or 3D that function as molecular breadboards. They could also function as switches or transducers, undergoing controlled nanomechanical motion, by exhibiting a conformational change in response to a stimulus. We create such DNA-based nanodevices for applications as high-performance ‘custom’ biosensors that intercept biochemical signals, thereby interrogating and reporting on cellular processes.

DNA-based nanomachines

DNA nanomachines are nothing but molecular switches. These are artificially designed assemblies that switch between defined conformations in response to an external cue. One of the devices made by our lab is the I-switch, which is a DNA nanomachine that undergoes a conformational change triggered by protons. Though it has proved possible to create DNA machines and rudimentary walkers, the first demonstration that they could function inside living systems came from our group. We showed that one could effectively map spatiotemporal pH changes associated with endosomal maturation both in living cells as well as within cells present in a living organism. We are making quantitative reporters of second messenger concentrations within living systems that will eventually position DNA nanodevices as exciting and powerful tools for intracellular traffic.

Multiplexing DNA nanodevices

Multiplexing DNA nanodevices

Eukaryotic cell function is tuned by an orchestrated network of compartments involved in uptake and secretion of various macromolecules. These compartments are functionally connected to each other via a series of controlled fusion and fission events between their membranes. One of the crucial determinants of this functional networking is the lumenal acidity of these compartments which is maintained by proton concentration, concentrations of different counter ions, membrane ion permeabilities and various ATP-dependent proton pumps. Maintenance of intraorganellar pH homeostasis is essential for protein glycosylation, protein sorting, biogenesis of secretory granules and transport along both secretory and endocytic pathways. Lack of probes reporting multiple pathways simultaneously has impeded understanding of intersection between the endocytic pathways. Therefore we have created a palette of DNA-based pH sensors compatible to various sub-cellular organelles such as the trans Golgi network (TGN), cis Golgi (CG) and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) of living cells as, each organelle has a different lumenal pH e.g., pHER is 7.2, pHCG is 6.6, while pHTGN is 6.3. We have engineered the I-switch to tune its pH responsive regime and now have I-switches specific for the ER, the Golgi and the late endosome and have successfully deployed two pH sensitive DNA nanodevices in the same live cell to measure pH in two different organelles simultaneously.

DNA Icosahedra for functional bioimaging

DNA Icosahedra for functional bioimaging

3D DNA polyhedra could have applications in drug delivery given that they have hollow internal cavities in which functional macromolecules may be housed and targeted. To this end we have shown that DNA can be used to make complex polyhedra such as an icosahedron, using a novel, modular assembly based approach. The power of this approach is that it allows the efficient encapsulation of other nanoscale entities in high yields. Many peptide based drugs cannot be delivered efficiently to their target due to degradation. Thus encapsulating them in non-leaky, programmable capsules such as DNA polyhedra might solve this problem. We have shown that this certainly works for bio-imaging agents, where FITC-dextran, a known pH-imaging agent could be encapsulated inside DNA Icosahedra and delivered effectively in a targeted manner in-vivo. We showed that post-encapsulation and post-delivery, cargo functionality was unaffected.

Naturally occuring Nucleic Acid Devices:

Naturally occuring Nucleic Acid Devices:

We are also interested in understanding naturally occuring nucleic acid based devices such as non-coding RNAs. RNA is an exciting and powerful biological medium for making genetically encoded, synthetic nucleic acid architectures that can probe and program the cell.

MicroRNA Biogenesis

Several naturally occuring nucleic acid based devices are nearly entirely composed of RNA: riboswitches, ribozymes and long non-coding RNAs to name a few. We also want to understand how some of these RNA based devices function, in the hope that we may someday be able to use the lessons learned to engineer smarter synthetic devices. MicroRNAs for example, are a class of RNAs that control gene expression by either by RNA transcript degradation or translational repression. Expressions of miRNAs are highly regulated in tissues, disruption of which leads to disease. But how this regulation is achieved and maintained is still largely unknown. MiRNAs that reside on clustered or polycistronic transcripts represent a more complex case where individual miRNAs from a cluster are processed with different efficiencies despite being co-transcribed. To shed light on the regulatory mechanisms that might be operating in these cases we considered the long polycistronic primary miRNA transcript pri-miR-17-92a that contains six miRNAs with diverse function. The six miRNA domains on this cluster are differentially processed to produce varying amounts of resultant mature miRNAs in different tissues. How this is achieved is not known. We show using various biochemical and biophysical methods coupled with mutational studies that pri-miR-17-92a adopts a specific three dimensional architecture which poses a kinetic barrier to its own processing. This tertiary structure could create suboptimal protein recognition sites on the pri-miRNA cluster due to higher order structure formation.

Selected References:

Selected References:

Chakraborty, S., Mehtab, S., Krishnan, Y.* The predictive power of synthetic nucleic acid technologies in RNA biology. Accounts of Chemical Research, 2014 , 47, 1710-1719.

Banerjee, A., Bhatia, D., Saminathan, A., Chakraborty, S., Kar, S., Krishnan, Y.* Controlled release of encapsulated cargo from a DNA Icosahedron using a chemical trigger. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 6854-6857.

Modi, S., Nizak, C., Surana, S., Halder, S., Krishnan, Y.* Two DNA nanomachines map pH of intersecting endocytic pathways. Nature Nanotechnology, 2013, 8, 459-467.

Krishnan, Y., Bathe, M. Designer Nucleic Acids to probe and program the Cell. Trends in Cell Biol. 2012, 22, 624-633.

Chakraborty, S., Mehtab, S., Patwardhan, A.R., Krishnan, Y.* Pri-miR-17-92a transcript folds into a tertiary structure and autoregulates its processing. RNA, 2012, 18, 1014-1028.

Surana, S., Bhatt, J. M., Koushika, S.P.*, Krishnan, Y.* A DNA nanomachine maps spatial and temporal pH changes in a multicellular living organism. Nature Communications, 2011, 2, 339.

Bhatia, D., Surana, S., Chakraborty, S., Koushika, S. P., Krishnan, Y.* A synthetic icosahedral DNA-based host-cargo complex for functional in vivo imaging. Nature Communications, 2011, 2, 340.

Krishnan, Y., Simmel. F. C. Nucleic Acid Based Molecular Devices. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 2011, 50, 3124 – 3156.

Modi, S., Swetha, M. G., Goswami, D., Gupta, G. D., Mayor, S., Krishnan, Y.* A DNA nanomachine that maps spatial and temporal pH changes in living cells. Nature Nanotechnology, 2009, 4, 325-330.

Bhatia, D., Mehtab, S., Krishnan, R., Indi, S.S., Basu, A., Krishnan, Y.* Icosahedral DNA nanocapsules via modular assembly. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 2009, 48, 4134 - 4137.

E-MAIL: yamuna@uchicago.edu

RESEARCH INTERESTS:

Nucleic acid-based Molecular DevicesBionanotechnology aims to learn from nature - to understand the structure and function of biological devices and to utilise nature's solutions in advancing science and engineering. Evolution has produced an overwhelming number and variety of biological devices that function at the nanoscale or molecular level. My lab’s central theme is one of synthetic biology, which involves taking a biological device, component or concept out of its natural cellular context and harnessing its function in a completely new setting so as to probe or reprogram the cell. Our research involves understanding the structure and dynamics of unusual forms of nucleic acids and translating this knowledge to create nucleic acid-based nanodevices for applications in biology.

Synthetic DNA nanodevices

Structural DNA nanotechnology is an emerging field that seeks to create exquisitely defined nanoscale architectures via the self-assembly of a set of carefully chosen DNA sequences. With a diameter of 2 nm and a helical periodicity of 3.5 nm, the DNA double helix is inherently a nanoscale object. The specificity and predictable affinities of Watson-Crick base pairing affords a hierarchy of molecular glues between given rods at defined locations that makes DNA an ideal nanoscale construction material. DNA nanodevices could either be rigid scaffolds in 1D, 2D or 3D that function as molecular breadboards. They could also function as switches or transducers, undergoing controlled nanomechanical motion, by exhibiting a conformational change in response to a stimulus. We create such DNA-based nanodevices for applications as high-performance ‘custom’ biosensors that intercept biochemical signals, thereby interrogating and reporting on cellular processes.

DNA-based nanomachines

DNA nanomachines are nothing but molecular switches. These are artificially designed assemblies that switch between defined conformations in response to an external cue. One of the devices made by our lab is the I-switch, which is a DNA nanomachine that undergoes a conformational change triggered by protons. Though it has proved possible to create DNA machines and rudimentary walkers, the first demonstration that they could function inside living systems came from our group. We showed that one could effectively map spatiotemporal pH changes associated with endosomal maturation both in living cells as well as within cells present in a living organism. We are making quantitative reporters of second messenger concentrations within living systems that will eventually position DNA nanodevices as exciting and powerful tools for intracellular traffic.

Eukaryotic cell function is tuned by an orchestrated network of compartments involved in uptake and secretion of various macromolecules. These compartments are functionally connected to each other via a series of controlled fusion and fission events between their membranes. One of the crucial determinants of this functional networking is the lumenal acidity of these compartments which is maintained by proton concentration, concentrations of different counter ions, membrane ion permeabilities and various ATP-dependent proton pumps. Maintenance of intraorganellar pH homeostasis is essential for protein glycosylation, protein sorting, biogenesis of secretory granules and transport along both secretory and endocytic pathways. Lack of probes reporting multiple pathways simultaneously has impeded understanding of intersection between the endocytic pathways. Therefore we have created a palette of DNA-based pH sensors compatible to various sub-cellular organelles such as the trans Golgi network (TGN), cis Golgi (CG) and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) of living cells as, each organelle has a different lumenal pH e.g., pHER is 7.2, pHCG is 6.6, while pHTGN is 6.3. We have engineered the I-switch to tune its pH responsive regime and now have I-switches specific for the ER, the Golgi and the late endosome and have successfully deployed two pH sensitive DNA nanodevices in the same live cell to measure pH in two different organelles simultaneously.

3D DNA polyhedra could have applications in drug delivery given that they have hollow internal cavities in which functional macromolecules may be housed and targeted. To this end we have shown that DNA can be used to make complex polyhedra such as an icosahedron, using a novel, modular assembly based approach. The power of this approach is that it allows the efficient encapsulation of other nanoscale entities in high yields. Many peptide based drugs cannot be delivered efficiently to their target due to degradation. Thus encapsulating them in non-leaky, programmable capsules such as DNA polyhedra might solve this problem. We have shown that this certainly works for bio-imaging agents, where FITC-dextran, a known pH-imaging agent could be encapsulated inside DNA Icosahedra and delivered effectively in a targeted manner in-vivo. We showed that post-encapsulation and post-delivery, cargo functionality was unaffected.

We are also interested in understanding naturally occuring nucleic acid based devices such as non-coding RNAs. RNA is an exciting and powerful biological medium for making genetically encoded, synthetic nucleic acid architectures that can probe and program the cell.

MicroRNA Biogenesis

Several naturally occuring nucleic acid based devices are nearly entirely composed of RNA: riboswitches, ribozymes and long non-coding RNAs to name a few. We also want to understand how some of these RNA based devices function, in the hope that we may someday be able to use the lessons learned to engineer smarter synthetic devices. MicroRNAs for example, are a class of RNAs that control gene expression by either by RNA transcript degradation or translational repression. Expressions of miRNAs are highly regulated in tissues, disruption of which leads to disease. But how this regulation is achieved and maintained is still largely unknown. MiRNAs that reside on clustered or polycistronic transcripts represent a more complex case where individual miRNAs from a cluster are processed with different efficiencies despite being co-transcribed. To shed light on the regulatory mechanisms that might be operating in these cases we considered the long polycistronic primary miRNA transcript pri-miR-17-92a that contains six miRNAs with diverse function. The six miRNA domains on this cluster are differentially processed to produce varying amounts of resultant mature miRNAs in different tissues. How this is achieved is not known. We show using various biochemical and biophysical methods coupled with mutational studies that pri-miR-17-92a adopts a specific three dimensional architecture which poses a kinetic barrier to its own processing. This tertiary structure could create suboptimal protein recognition sites on the pri-miRNA cluster due to higher order structure formation.

Chakraborty, S., Mehtab, S., Krishnan, Y.* The predictive power of synthetic nucleic acid technologies in RNA biology. Accounts of Chemical Research, 2014 , 47, 1710-1719.

Banerjee, A., Bhatia, D., Saminathan, A., Chakraborty, S., Kar, S., Krishnan, Y.* Controlled release of encapsulated cargo from a DNA Icosahedron using a chemical trigger. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 6854-6857.

Modi, S., Nizak, C., Surana, S., Halder, S., Krishnan, Y.* Two DNA nanomachines map pH of intersecting endocytic pathways. Nature Nanotechnology, 2013, 8, 459-467.

Krishnan, Y., Bathe, M. Designer Nucleic Acids to probe and program the Cell. Trends in Cell Biol. 2012, 22, 624-633.

Chakraborty, S., Mehtab, S., Patwardhan, A.R., Krishnan, Y.* Pri-miR-17-92a transcript folds into a tertiary structure and autoregulates its processing. RNA, 2012, 18, 1014-1028.

Surana, S., Bhatt, J. M., Koushika, S.P.*, Krishnan, Y.* A DNA nanomachine maps spatial and temporal pH changes in a multicellular living organism. Nature Communications, 2011, 2, 339.

Bhatia, D., Surana, S., Chakraborty, S., Koushika, S. P., Krishnan, Y.* A synthetic icosahedral DNA-based host-cargo complex for functional in vivo imaging. Nature Communications, 2011, 2, 340.

Krishnan, Y., Simmel. F. C. Nucleic Acid Based Molecular Devices. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 2011, 50, 3124 – 3156.

Modi, S., Swetha, M. G., Goswami, D., Gupta, G. D., Mayor, S., Krishnan, Y.* A DNA nanomachine that maps spatial and temporal pH changes in living cells. Nature Nanotechnology, 2009, 4, 325-330.

Bhatia, D., Mehtab, S., Krishnan, R., Indi, S.S., Basu, A., Krishnan, Y.* Icosahedral DNA nanocapsules via modular assembly. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 2009, 48, 4134 - 4137.

CHENNAI, TAMILNADU, INDIA

Chennai - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chennai

.

.

///////////

No comments:

Post a Comment